Being OK with Not Being OK (Part 1: Identifying What Is)

Problem-Solving

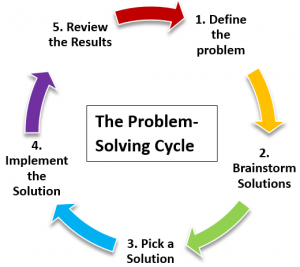

There is a prevalent and almost ubiquitous social conversation around solving problems and “getting results” in our society. Since our earliest education in the school system we are given problems and instructed as to how to solve them. Our intelligence is judged largely by our aptitude to problem solve, to think critically, to come up with solutions. My university education essentially trained me to think analytically, to form logical arguments and back them up with evidence – to find solutions and make sure they were well fortified. This type of thinking, this analytical thought process, is useful for many tasks in this world; some of humanity’s highest achievements have come as a result of using these problem solving faculties of ours. When it comes to dealing with matters of spiritual growth and development, however, analytical thought can be a great detriment.

There is a prevalent and almost ubiquitous social conversation around solving problems and “getting results” in our society. Since our earliest education in the school system we are given problems and instructed as to how to solve them. Our intelligence is judged largely by our aptitude to problem solve, to think critically, to come up with solutions. My university education essentially trained me to think analytically, to form logical arguments and back them up with evidence – to find solutions and make sure they were well fortified. This type of thinking, this analytical thought process, is useful for many tasks in this world; some of humanity’s highest achievements have come as a result of using these problem solving faculties of ours. When it comes to dealing with matters of spiritual growth and development, however, analytical thought can be a great detriment.

If there’s any lesson I’ve learned from my own experience in facing personal demons and overcoming obstacles within myself it’s this: growth can be very painful. When dealing with matters of the soul, especially when compounded with mental health issues (of which I am no stranger), the terrain can often be treacherous and the path uncertain. The experience of going through personal transformation can be confusing and downright terrifying, and it almost never happens overnight. The reality is that there is often a great deal of pain and suffering that goes with this thing we call being human, whether it’s an undercurrent to our daily lives or it sticks out right in our faces. And for those who are in the midst of acute suffering for which there is no easily identifiable cause, no amount of immediate, pragmatic, goal-oriented problem solving is going to make much of a difference.

No Formula

There is no formula for spiritual growth and no guarantee when it comes to transformation. There are many systems and schools of thought as to how the process of human growth and development occur in one’s life, and there is much common wisdom to be found in the various philosophies, religions, and cultures of the world. Each human being, however, is unique. As much as we have in common  with each other as a species and as similar as some of us may appear to be, we all have a unique set of circumstances that make us who and how we are. From our genetic codes to our upbringings to our beliefs and convictions, no two people are exactly identical. We don’t go through things in exactly the same ways, at precisely the same times, or for an identical set of reasons. For this reason, while we may find solace in certain ideas presented by others and compassion, understanding, and even empathy from those we encounter, it is close to impossible for two people to ever fully be in the world and experience reality in exactly the same way.

with each other as a species and as similar as some of us may appear to be, we all have a unique set of circumstances that make us who and how we are. From our genetic codes to our upbringings to our beliefs and convictions, no two people are exactly identical. We don’t go through things in exactly the same ways, at precisely the same times, or for an identical set of reasons. For this reason, while we may find solace in certain ideas presented by others and compassion, understanding, and even empathy from those we encounter, it is close to impossible for two people to ever fully be in the world and experience reality in exactly the same way.

At the end of the day, when we are experiencing the pains of our particular human existences, there will always be some degree to which we are alone. This is not to say that there can’t be great comfort in sharing our thoughts and feelings with others and connecting with other people – great relief and joy can be derived from human interaction, especially in times of emotional turmoil. My point is that there’s some part of our experience that will always remain so inherently subjective that no amount of conversation, analysis, or investigation will reveal it fully to the mind of an observer. This is why it is so important for us as human beings to learn to be in tune with ourselves as we truly are, in ways that only we can know ourselves.

Accepting What Is

So brings us to the most important and greatest challenge of being human: to be OK with those parts of ourselves that nobody else can truly know. It is possible, although not realistically feasible, to acquire evidence from the external world as to the goodness, validity, or “OK-ness” of almost every aspect of ourselves. Others can tell us that we are good people, that we are worthwhile, or make a list of our traits for us, but no external description or account can fully encompass all that we truly are. The parts of ourselves that only we can know intimately, provided we are thoroughly honest with ourselves and that we have the sufficient insight into our own psyches, are beyond the purview of anyone but ourselves. If we are to have a significant and lasting respite from suffering, or even a chance at true fulfilment in life, we must learn ways to be OK with our deepest depths – the secret parts of us that nobody else can see.

Distinguishing

The first step in the process of learning to be OK with ourselves is to identify that which is the cause of our pain; we need to know what it is that we are not OK with. It could be depression, anxiety, or some form of mental illness, or some kind of compulsive behaviour, insecurity, or fear that we carry around and are unable to get rid of. Regardless of what it is, the experiences or feelings that are causing us to suffer must be identified and characterized in some way that makes sense to us. For lack of a better term, the syndrome that we possess within us that is the source of distress needs to be distinguished and named. We need to be able to identify it as something that is, at least for the  moment, intrinsically linked to ourselves, but at the same time is something that is not us. A person with depression, for example, must be able to distinguish themselves from their depression. It may be something that encroaches on every aspect of their experience of life and has real, tangible consequences, but nonetheless the person in their entirety cannot be said to be the same as their depression. Said another way, the person must acknowledge that they have depression, that the depression is linked to them, but they as a person are nonetheless distinct from their depression.

moment, intrinsically linked to ourselves, but at the same time is something that is not us. A person with depression, for example, must be able to distinguish themselves from their depression. It may be something that encroaches on every aspect of their experience of life and has real, tangible consequences, but nonetheless the person in their entirety cannot be said to be the same as their depression. Said another way, the person must acknowledge that they have depression, that the depression is linked to them, but they as a person are nonetheless distinct from their depression.

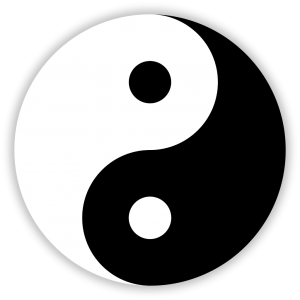

It can be quite difficult to distinguish oneself from the syndrome being experienced, especially when we are talking about matters of the mind. When lost in the whirlwind of thoughts, feelings, sensations, perceptions, and the like which make up our conscious experience, especially when the totality of such experiences are intense, confusing, or painful, it can be very hard to maintain a distinct sense of selfhood. Perhaps the greatest danger is to identify too much with one particular thought, feeling, internal voice, thought-pattern, or aspect of experience such that it becomes indecipherable from one’s true self. It should also be noted that the purpose of distinction of oneself from one’s experiences is not to cut off or completely compartmentalize one’s experiences. In the same way an arm or leg is part of us, our thoughts and feelings are part of us. It would be strange, however, if one were to say, “I am my leg” in an indefinite sense. The totality of what makes a person who they are cannot be restricted to one particular experience or syndrome. It is when a person completely identifies with one’s suffering as who they are or wholly indistinct from themselves that the suffering becomes unbearable. Conversely, if one perceives one’s experience of suffering as completely outside their control, as if their syndrome has all the power to continually inflict itself upon the sufferer, that hopelessness and despair may also become a reality.